The Edutopia article “Responding to Disruptive Students” supplement

Behavior is communication. Not only students’ behavior can be challenging.

In fact, the only behavior we can change is our own.

Learn how to manage behavior in your classroom with this self-awareness exercise.

My experimental and rather provocative article “Responding to Disruptive Students” published on Edutopia scored over two hundred thousand views (August 2021) and had huge resonance on social media. Many thanks to George Lucas Educational Foundation and Edutopia’s editorial staff for the opportunity to measure my thoughts on educators’ behavior with their large and very competent audience.

I decided to write this supplement to answer the numerous comments and questions the dedicated educators, friends, and passionate readers left on Edutopia and Edutopia’s Facebook page.

The article is about helping educators who work with challenging early childhood students to recognize and avoid their unwittingly negative attention while teaching.

New readers are welcome to enjoy “Responding to Disruptive Students” before continuing here.

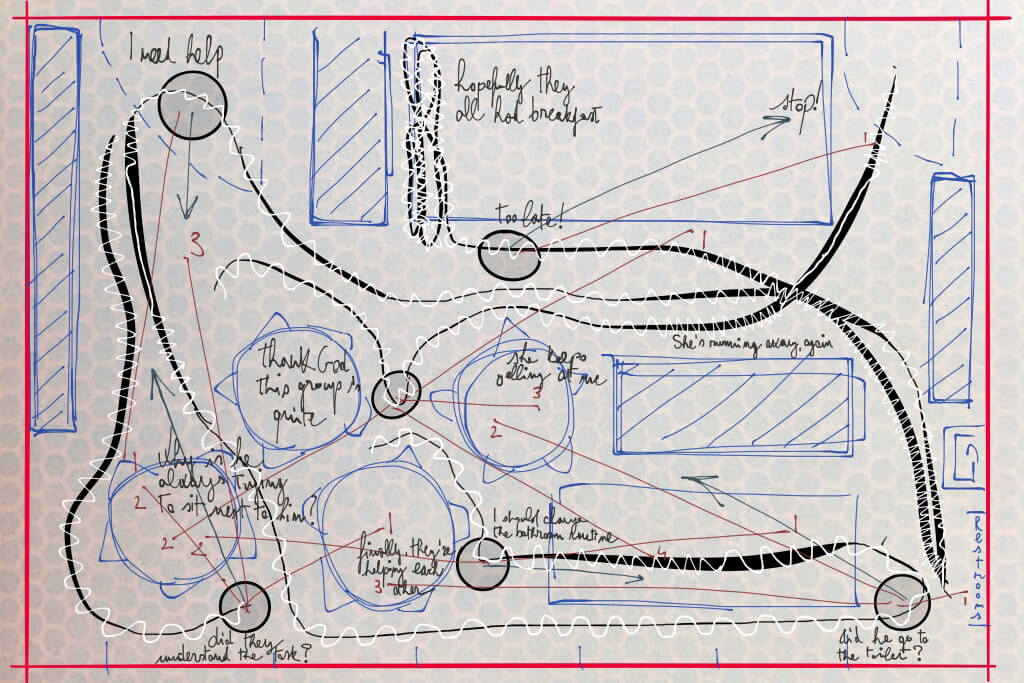

Mapping Your Behavior in the Classroom

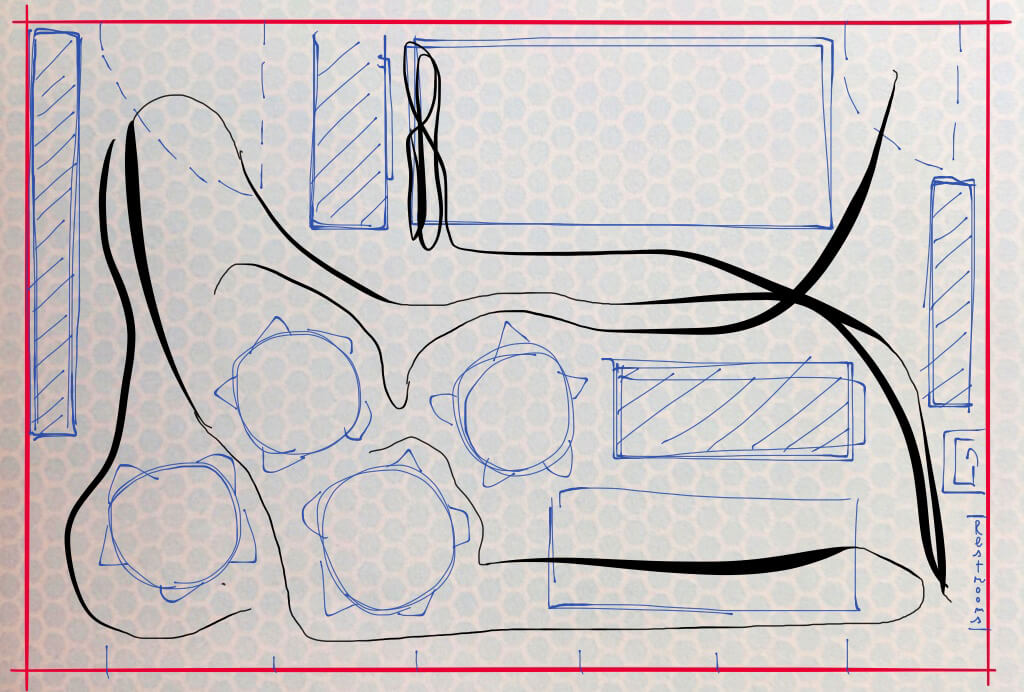

It is worth beginning with the core of the Edutopia article, the Map. While presenting the Map, I’ll answer readers’ comments and questions related to its implementation.

The average Edutopia reader accesses that website on a smartphone or tablet. For this reason, one of Edutopia’s editors suggested publishing only Step Five of my five-step map, because “unfortunately, the images you have included won’t be easy to make out on mobile devices.” Got it. In the future, I’ll work on more smartphone responsive graphs. For now, let’s get started.

Step One: Design Your Classroom and Trace Your Path Through It

The setting for a change in behavior is the classroom itself, which I call a ‘learning environment.’ A learning environment is a normal classroom that has reached its full potential. It is a space that every educator knows perfectly, trusts implicitly, sets up, and constantly re-designs to accommodate the needs of each individual. It is the space where every move, every look, and every breath is communication and forms part of the learning process.

You only need paper and three pens or pencils in different colors.

Sketch doors, windows, all the desks, boards, activity centers, the sink, rugs, computers, and other significant items. Remember to sketch your own desk and chair too. I’m sure you’ve already got a clear idea of where the most challenging students usually sit or gravitate. You’ve probably also already heard the door slamming while you were drawing it.

Now, imagine teaching class on a regular day. It is irrelevant whether your students are stationary or in constant motion across a project-based setting. The number of students in a classroom is also negligible.

If you work in multiple classrooms, begin with your favorite one. Trace a line of the path you take across the classroom. You might discover that your motion has a specific shape or pattern. Do you sometimes speed up for a particular reason? Draw a bold line on the map wherever you usually have to hurry your pace.

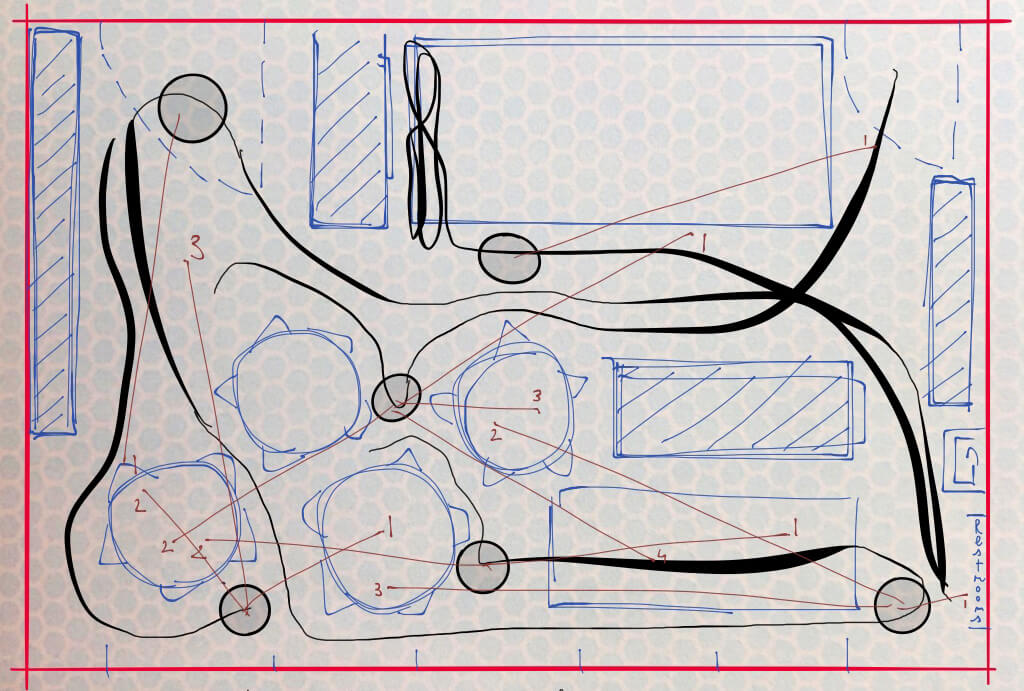

Draw a circle on the line to mark each stop you make on your journey. From each circle, trace a line with another color to represent your initial glance from that position. Who or what are you looking at? Continue tracing lines to match every glance you remember being part of your everyday ‘observing’ routine.

Step Two: Mark All the Stops and Glances On Your Way

If you usually teach sitting down, begin your map by tracing the lines of your glances from the place where you usually sit.

If you raise your voice, draw arrows tracing the direction and target of each exclamation.

Step Three: Trace Arrows to Represent Your Exclamations

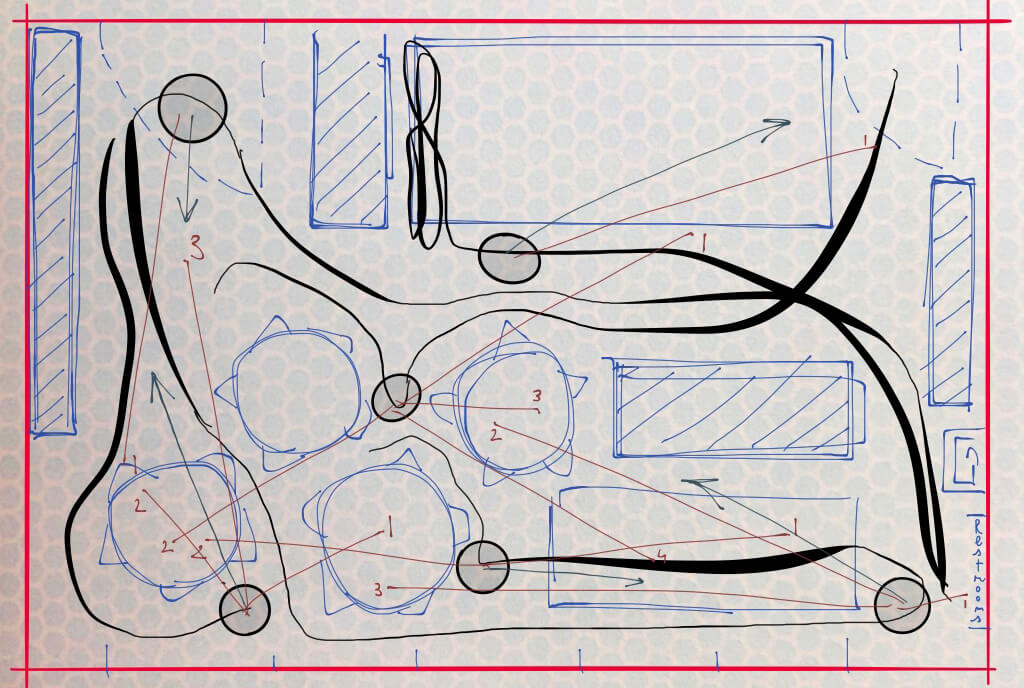

Are you conscious of the way you breathe during class? Use a new color and draw a wavy line on top of the lines and arrows you have already sketched. You have now mapped your path, pace, glances, and exclamations. Does the wavy line always look regular, or have you also traced some chaotic or nervous zig-zags? Could it be that you’ve sometimes forgotten to breathe? In this case, use the same color to trace a flat line for your ‘apnea’ moments.

Step Four: Trace Wavy Lines to Understand How You Breathe

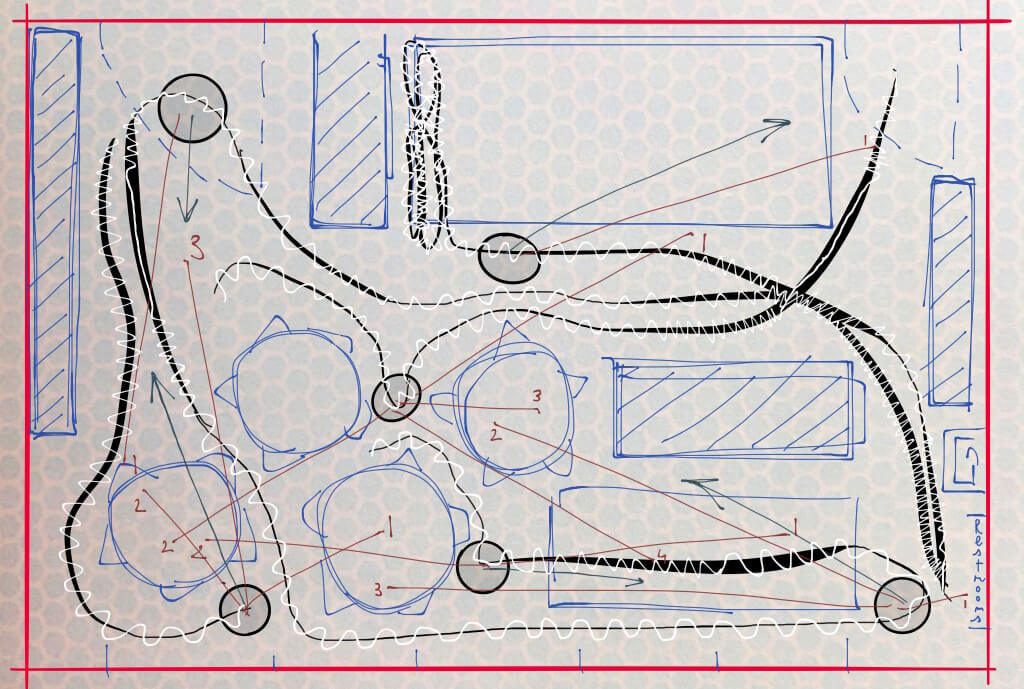

Add your thoughts. Can you remember a frequent thought you have during class? Does it concern all of your students, or one student in particular? Write your recurrent thought on the map close to that student’s desk. Repeat this for every student where you have a specific thought. Do your thoughts refer to yourself? Write them down on the map exactly at the spot where each one comes to mind. Do the same if your thoughts relate to the class as a whole. Now you’ve finished. Have a look at your map. This is you in your classroom.

Step Five: Add Each Thought To The Place It Occurs

Why Map?

To understand both negative attention and challenging behavior educators can shift target and begin looking at themselves within their learning environments. The Map is the easiest and most convenient way I know to do this. After going through this process and recognizing their own behavioral patterns, educators can begin working on their relationship with challenging students.

You have just mapped your movements, your breathing, and your thoughts: welcome to emotional data.

Your Main Objection: Who has time for mapping?

Self-awareness is a powerful tool for those who have to manage complex situations. Teachers and educators do an incredible job every day; they never stop giving to students. Adding another task – mapping – might feel impossible. However, you only need about ten minutes to draw your map, and these ten minutes are for you. Mapping brings positive changes to your classroom because it makes your life a little easier. It’s a win-win.

Some educators find time for themselves early in the morning; some enjoy having a break in the silence of the school library between classes; other educators write reports at the end of the day and add one more task to their to-do list: the map. Ten minutes. If you need a break while correcting assignments or tests, sketch the map. It is a one-time exercise.

Check out Embodied Learning training programs focusing 'Challenging Behavior'

-

Behavior is Communication

-

Learn how to observe and transform behavior as an educator and assistant to children

-

Learn how to approach children’s challenging behavior through embodied cognition

-

Learn how to control your own behavior and make an impact in your classroom

On Titles and Editorial Stock Photos

Some readers felt engaged more by the title of the article and also by the editorial stock photo that introduces it than by the content itself.

The original title I gave to the piece was: ‘Breaking the Worst “Challenging” Behavior: How Educators Can Recognize and Avoid Their Unconscious Negative Attention.’ Originally, the article’s opening was a quotation inspired by everyday life in a classroom: “Can you for once stop dangling around like a silly spring, sit properly and finish your assignment?” This sentence helped to sum-up what kind of negative attention I was referring to during the entire article.

My goal is to help educators and teachers approach challenging students through a higher level of self-awareness and self-confidence and create a new stronger ally: the learning environment. I wrote my article focusing on the educator. I never mentioned the student deliberately. In fact, I do not ever refer to students as “disruptive”.

I wanted the article to be read by a large, informed audience. For this reason, I presented my draft to Edutopia’s staff, who edited my work and selected the stock photo to popularize it on the web. It worked.

Tracking Emotional Data

William Kentridge’s collage “Parcours d’Atelier” and information designer Giorgia Lupi’s work were the inspiration for both article and Map, since valuing emotional data is at the core of their artistic and professional research.

In my opinion, visualizing an educator’s journey to self-awareness, i.e. drawing a map, is the first step in understanding the complex system that is challenging behavior in the classroom.

As part of the on-going research on how to relate more successfully to new generations of children and their social environment, I heartily support a bottom-up approach. Collecting the information we have helps to avoid any prejudgment and adult ‘mistakes’ in learning environments.

Bibliography

The best guide we have to approach challenging students:

Nancy Rappaport and Jessica Minahan, The Behavior Code: A Practical Guide to Understanding and Teaching the Most Challenging Students (Cambridge: Harvard Education Press, 2013)

The best source to understand what emotional data is and how to collect it:

Giorgia Lupi and Stefanie Posavec, Dear Data (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2016)

The best art catalog on visualizing self-awareness:

William Kentridge, Everyone Their Own Projector (Valence, France: Captures Edition, 2008)